Decades have passed since anyone enquired about my external boundaries. That they once enquired and then stopped feels consequential. Those external boundaries were not just departmental divides. They were interactive places where creative tensions played out: fringe theatres of conflict, movement and transformation where actors and audiences co-produced solutions to complex problems. These boundaries shaped my profession and how we were perceived, how we operated, and how we were held accountable.

Today, looking in from the external boundaries of the criminal justice system, movement and transformation feel almost impossible. At the boundary between custody and community, those fringe theatres appear to have become unsafe, precarious fault-lines characterised by overcrowded prisons, overstretched probation caseloads, under-supported teams, and under-served populations. Meanwhile, families and communities are left to absorb the shock.

We didn’t arrive here by accident. Those of us in leadership positions designed in much needed clarity and control but inadvertently designed out collaboration and community. We embraced market forces, believing they would make the system stronger. But in so doing, we exposed key areas of vulnerability. It was never the intention to make the system more fragile and fragmented by eroding the spaces where learning and shared ownership once unfolded. Nevertheless, fragmentation and fragility are unfortunate by-products of decades of systems change.

I distinctly remember it being one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Probation who asked me about my external boundaries. This was on the back of a conversation we were having about my self-motivated litter-picking around the perimeter of the probation centre I worked at. I was recounting the salutary lesson I learned retrieving crumpled worksheets – unsolicited feedback that, alongside high attrition, prompted me to explore better ways to engage: more collaboration, more co‑production; less litter‑picking.

Things were different in those days. Probation officers were social workers grounded in the teachings of Pincus and Minahan among others. We operated as viewfinders, intuitively reframing interdependencies and making sense of complexity: routinely ‘thinking systems’ before ‘systems thinking’ was widely recognised as a discipline. I don’t recall our being specifically resourced to think this way, but we were trained and supported, and the thinking was embedded.

Back then, as a fresh-faced frontline probation officer, I had a sense that I belonged to that important human interface between systems (the space where support should hold but can’t if it’s left to its own devices, the space between courts and communities, enforcement and support, containment and change) and between people and situations that were stuck and would be better if they were unstuck.

We knew, and our regulators also recognised, the importance of navigating and negotiating external boundaries between systems, and the imperative to form meaningful connections between the people we worked with and the systems that affected their lives. At those outer edges lay fertile ground for learning, development and creativity. Getting our external boundaries sorted meant seeing what was real, sitting with and feeling live tensions, and shaping tangible new ways of relating to the world as it actually presented, as opposed to pretending how it might be.

Most importantly, we were connecting with what mattered to people and communities in ways that felt meaningful and relevant to them.

Even then, our operating environment was dominated by a polarising ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ debate. Then, as now, ‘hard’ meant easy to pin down, isolate and control. Meanwhile, ironically, given the term, ‘soft’ meant difficult to make sense of, to disentangle, and to tame. ‘Hard’ was also associated with toughness. Things that sounded tough sounded tangible and credible. On the other hand, things that didn’t come across as immediately punitive were perceived by some as ‘soft’ – lax and indulgent. So words like ‘robust’ and ‘intensive’ entered the policy lexicon as a means of building credibility and public confidence.

This portrayal jarred with those of us whose professional practice had always taken place within the confines of a resilient yet nuanced framework, held together at its corners by four key principles:

This four‑cornered framework carried far more weight than one‑word labels – no matter how ‘robust’ or ‘rigorous’ those words might have sounded. The work was neither hard nor soft. It meant working with people, holding them to account and holding on to hope at the same time, knowing when to enforce and when to enable, when to challenge and when to stand alongside. We figured that safety and change typically came out of connection rather than control and, in that context, confidence came through the power of relationships, not through the power of rhetoric.

Nonetheless probation was evolving from a welfare-orientated service to a risk-focused one. This trajectory was being driven by mounting evidence of what worked with different cohorts and growing intel on predictive and malleable criminogenic factors associated with offending. Hence my peers and I supported a change in strategic direction that heralded a system-wide transition under the banner of ‘what works.’ This change was underpinned by primary legislation when the Criminal Justice Act 1991 was enacted.

We realised we had to get our Act together. The welfare-focused model was, in reality, light on evidence and consistency. Practice varied widely, particularly in relation to the duty of compliance with court orders. Inspections and audits repeatedly found ambiguity of purpose between care and control. And without proper tools to support assessment and planning, it was difficult to show reliably and publicly how and why our efforts made a tangible positive difference to reoffending outcomes.

So, framed around the principles of risk, need and responsivity, gut feel and intuition were replaced by actuarial assessment. Targeted levels of service and structured (later to become accredited), manualised and evidence-based interventions sharpened the focus on measurable reductions in reoffending. Autonomous, individualised practice and systems thinking gave way to programmed delivery at scale, publicly presented as ‘punishment in the community’. Yet ‘punishment’ was balanced by ‘community’ which, for many of us, continued to sit at the bedrock of our work.

This policy-led, evidence-informed transformation was followed by successive waves of reform, notably, the nationalisation of the probation service in the early 2000s and the merger of prison and probation services under the umbrella of the National Offender Management Service (NOMS) just a few years later. These changes coincided with wider public sector reforms and a leadership culture steeped in market-based principles, managerialism, performance metrics, and (later) payment by results. In this context, acting on the commercial impulse to structure out the boundary between custody and community made complete sense: it meant tightening control over outputs. However, the inconvenient truth that existed then – just as it does today – was that many offence reduction outcomes were cultivated inside communities, across systemic boundaries, not just inside prisons or probation centres.

As marketisation took hold, some innovative projects set out to square the circle between commerciality and community. One that I led was a NOMS‑funded pathfinder across the West Midlands. Evaluated by Aston Business School, the programme applied branding disciplines to Community Payback with a view to matching unpaid work to offence type and local need across four strands – victim reparation, community enterprise, public resource optimisation, and environmental concerns. From this we learned that a clear master brand for Community Payback, paired with locally meaningful projects, worked better than rigid sub‑brands. People valued the impact that they could see and leverage in their community.

The next tidal wave of transformation was not driven by the greater good of the community. Transforming Rehabilitation soon became a missed opportunity to involve the voluntary and community sector in a real and meaningful way. This market-led, risk-based, performance-focused, boundary-splitting experiment caused many of the widespread systemic issues that still ripple across the system today.

Over the years the systems, and the leaders like me who played their part in them, adapted to, fed into and fed off all these seismic changes: the transition from social work to public protection, the incremental focus on reducing reoffending, and the increasing marketisation of probation which led to nationalisation, centralisation, privatisation and, finally, renationalisation.

Restorative and relational approaches as well as desistance research have outlived these reorganisations, despite being under-resourced – reminding us that systems change is fundamentally relational. Yet history shows that external boundaries define what lies inside the system and what lies outside it. These boundaries also regulate the flow of interaction between the two. Accordingly, those edgy, improvisational spaces where systems once met, and where people co-produced, adapted, and learned in real time, have been replaced by rigid, highly regulated, tightly specified interfaces governed by contracts, guiding policies, performance metrics and supply chains.

The cumulative effect is one of insulation not integration, of containment not collaboration. The drive to pin down, isolate and control efficiencies and outcomes has, over time, made the external boundaries between sectors, services and systems taller, wider and harder. Each organisation, each professional domain, each layer in the supply chain has become more inward facing: focusing on their own targets, their own margins and risks, their own sustainability. Learning has become siloed and stratified. Cross-boundary working has become transactional, not relational. Whole systems approaches are squeezed into service specifications, project plans and operating schedules. Systems thinking rarely sets the context for how power is shared, how decisions are made, how money flows, and how system-wide outcomes are achieved, measured and celebrated.

The closer people are to the outer edges of the system, the more they have to lose from boundary hardening, for example:

Yet these losses are not isolated. They appear in every recall or reconviction, in every recruitment or retention crisis, in every victim impact statement, in every community group’s annual return, and in every additional drawdown on public funds. This picture is confirmation, decades on from my meeting with the probation inspector, that we still don’t have our external boundaries sorted.

There are some inspirational system leaders that champion partnership principles, collaborative commissioning models and joined-up service strategies. On some frontlines, new roles and workstreams aim to counter gaping holes and inbuilt impediments, reach deeper into communities and strengthen support pathways. Beyond these boundaries, I meet resourceful people who continue to find new and innovative ways to keep going while systems look after themselves. These people build what they can with the resources they have at their disposal: circles of trust and hope, networks of care, and campaigns for change. They co-produce support without contractual stability. They piece together funds from voluntary sources to reach ever more people despite not being able to recover the cost.

Yet as we all know, none of this is sustainable without cost. Practitioners risk being pulled in opposing directions, for example, taking risks to build trust while holding back to meet guidelines, and working relationally inside a system that prioritises transactional compliance. In my experience, there is only so much weight practitioners can carry in terms of complexity, confusion and moral dissonance without needing to regroup, reflect and reimagine. Meanwhile, on the other side of the boundary, holding things together without recognition, mandate or adequate resources is invariably exhausting in an atmosphere characterised by uncertainty and firefighting.

To draw these margins as fortresses and monoliths is a strategic choice. It doesn’t have to be this way. These manufactured structures are not immovable or irredeemable. We find the balance between protection and connection only if we keep inspecting our external boundaries. This should be an ongoing prioritised conversation, not a one-off event when an inspector calls.

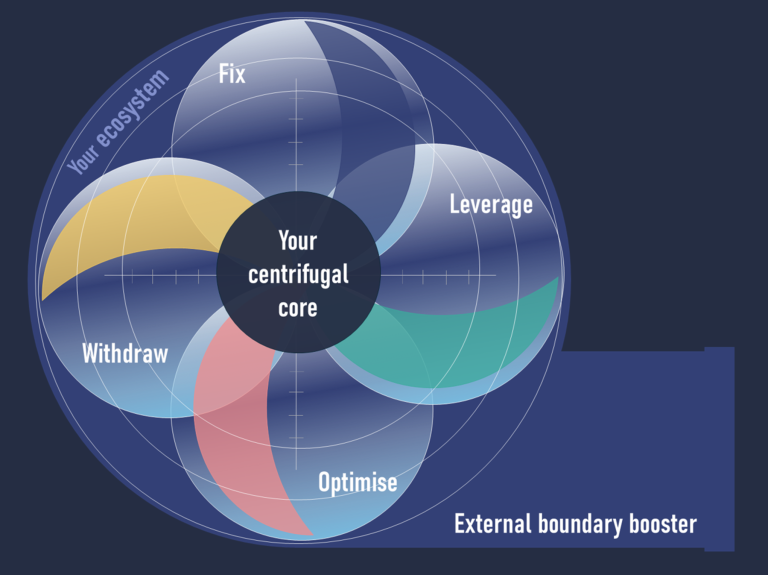

Safeguarding external boundaries should be core leadership work. It is just as important in the boardroom and at the policy table as on the frontline. Yet this key strategic choice is often overlooked, with regard to its transformative potential. Choosing to think deeply and differently about the outer edges of the systems that we operate in – where systems meet, where people navigate complexity, and where innovation can take root – creates room to address key challenges in justice, health, and social care. From the outside in, an organisation’s external boundaries are where real strategies and business plans take shape – the ones that stand up to scrutiny and last. Propositions, funding applications, and bids and tenders also spring to life on these boundaries, especially when community-led support networks are properly leveraged and resourced.

I liken the reclamation process to laying down pavements of possibility: creating walkable, workable spaces where people can meet, move forward in a direction, at a pace that suits them, and where everyone contributes to the conversation; crucially, no one owns it. Pavements aren’t always easy to navigate. People jostle and bump into one another from time to time, but there is generally room for everyone. And when a pavement opens out into a wider space, new possibilities appear where we can:

Whilst this is not a mandate, we all have to pay attention to external boundaries. I didn’t need permission to start picking litter around the boundary. My actions were fuelled by curiosity: why was group attendance dropping, and why wasn’t key content landing? I stopped, thought, learned, and then invited others in to help me work out a better way of working.

Looking back, more should have been done during successive criminal justice transformations to sort out and preserve our external boundaries – not as neat, tidy and regimented lines, but as flexible, permeable crossings that ebb and flow to address multiple challenges and variations, and to achieve shared outcomes in a messy world. We can but imagine the difference it might have made had capable boundary stewards been present at the fault lines to read the early tremors and act early to prevent the kind of rupture that shakes trust and hardens the boundary for years.

But we are where we are. As the current custodians of the boundary, we must all decide its future. The choices we make will shape the transformative power of the opportunities that we create with people and communities in the beautiful, bewildering space that lies beyond the boundary.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |